A disciple of Hillel, the 1st-century rabbi who founded a dynasty of scholar-sages, exhorted students struggling with a perplexing passage from the Torah not to give up but to “turn it and turn it, for everything is in it.”

Good journalistic narratives are like that—the wider world is revealed in a small story that conveys how lives, cultural trends and social movements converge in a specific time and place.

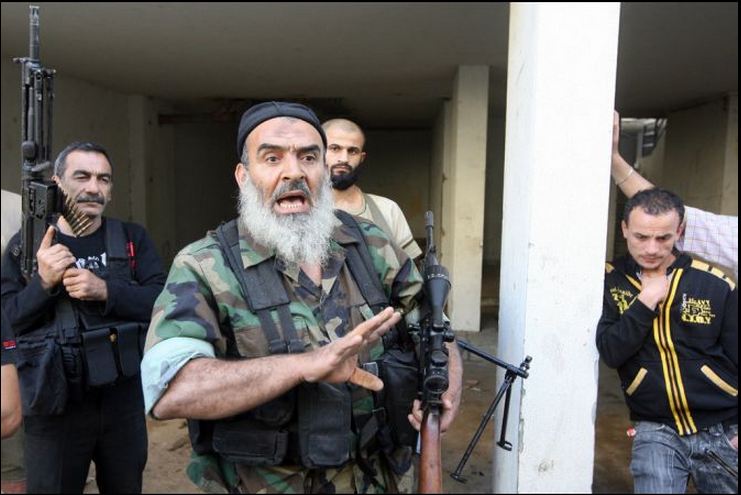

Take, for example, Carlotta Gall’s recent New York Times profile of a young Tunisian man who swapped the stability of a simple but promising life for the jihadist’s ardor and sense of transcendent purpose.

We learn that 17-year-old Aymen Saadi was good at math, and that his parents—a primary school teacher and agricultural engineer—hoped he would follow his older brother to university.

But Tunisia, cradle of the Arab Spring, remains a restive place. A relatively moderate Islamist government has responded with an iron fist to challenges from orthodox religionists who are waging violent campaigns to impose a strict interpretation of Islamic law both at home and in other destabilized Muslim-majority countries.

Amid this flux of influences Aymen began to find a sense of identity and purpose at a Salafist mosque that reportedly serves as an unofficial recruiting center for militants with ties to like-minded groups in Syria, Libya, Mali and elsewhere.

The article doesn’t pinpoint the Salafi movement in the spectrum of Islamic belief, an omission akin to identifying Opus Dei simply as a Christian sect rather than placing it within the recent historical context of the Roman Catholic Church. And the name of the primary vector for Salafism in Tunisia—Ansar al-Sharia (Partisans of Islamic Law)—begs for some clarification. Under the governing Islamist party, moderate interpretations of Islamic law already shape many aspects of daily life in the country, but as in much reporting on Sharia in Western news media, this important bit of nuance is missing from Gall’s piece.

Still, Gall has performed a valuable service by highlighting the nested relationships among Aymen’s story, social instability in Tunisia, other current conflicts in the Middle East and the broader chronicle of proxy wars in the region. This fine-grained attention to context and history is often absent in stories in which religion shapes the narrative—though having the curiosity and patience to turn such stories even just a little can make the difference between mere filler and a potential Pulitzer.