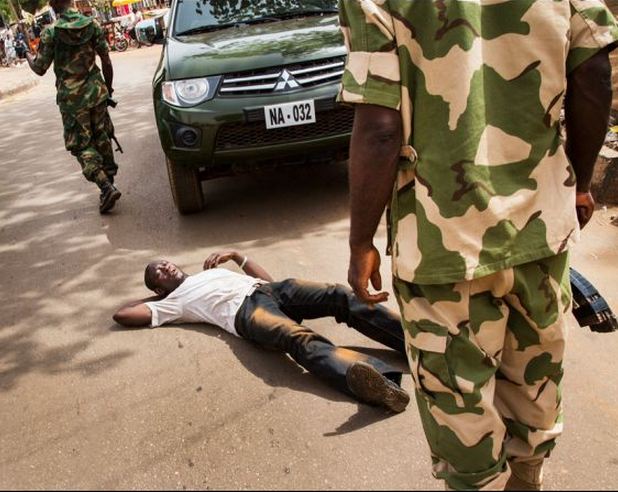

Nigerian Army forces man a checkpoint to protect Sunday Christian prayer services in Sokoto, Nigeria on April 14, 2013, where less than 5 percent of the population is Christian. (Ed Kashi/VII/GlobalPost)

Modern Nigeria emerged through the merging of two British colonial territories in 1914. The amalgamation was an act of colonial convenience. It occurred mainly because British colonizers desired a contiguous colonial territory stretching from the arid Sahel to the Atlantic Coast, and because Northern Nigeria, one of the merging units, was not paying its way while Southern Nigeria, the other British colony, generated revenue in excess of its administrative expenses.

It made practical administrative sense to have one coherent British colony rather than two. It also made sense to merge a revenue-challenged colonial territory with a prosperous colonial neighbor, so the latter can subsidize the former.

The amalgamation made little sense otherwise and has often been invoked by Nigerians as the foundation of the rancorous relationship between the two regions of Nigeria. Northern Nigeria, now broken into several states and three geopolitical blocs, is largely Muslim. It was the center of a precolonial Islamic empire called the Sokoto Caliphate, and its Muslim populations, especially those whose ancestors had been part of the caliphate, generally look to the Middle East and the wider Muslim world for solidarity and sociopolitical example. The South, an ethnically diverse region containing many states and three geopolitical units, is largely Christian. The major sociopolitical influences there are Western and traditional African.

Moses Ochonu, associate professor of African history at Vanderbilt University, traces the roots of the conflict between Nigeria’s Christian and Muslim populations for GlobalPost’s Special Report, “A Bridge in Kaduna: Crossing Nigeria’s Muslim Christian Divide.”